The following is an original paper submitted by Bruce W. Abugel, President, Enercon Group, Inc. at the IP's first Loss Control Forum held in London in October 1985. It is from the book Oil Loss Control in the Petroleum Industry published by Wiley Press.

LOSS CONTROL GROUPS - PROGRAMMED TO FAIL?

The term "loss control" is not new or unique to the petroleum industry and its pure definition has encompassed a broad range of disciplines from safety to accounting. In the context of this paper, however, we will limit its scope somewhat to be the process of reducing or eliminating the loss exposure an entity has with regard to an oil movement or movements either on a spot or continuing basis.

Loss exposure may be defined as the value of the loss actual or potential- that an entity involved in an oil transaction may be liable for during that particular transaction or for a cumulative period. Accordingly, loss control groups are those persons or person within a particular organization who are given the responsibility of assuring their company's loss exposure is minimized.

The need for loss control can usually be justified by making analysis of loss exposure for a subject business entity that does not already have such a group. Such an analysis shows oil volumes moved by the particular entity, by what means, and what their exposure is at each phase of the movement. In most cases, it shows the entity has an alarmingly high loss exposure.

Enercon Group Inc. has performed a number of these analysis for clients, and if we make a comparison of the described analysis of ten major/independent oil and shipping companies, we find that their loss exposure was more often than not, directly related to the number of movements they had; and that the value of their exposures in simplest terms ranged from 8 to 75 million dollars each, per annum.

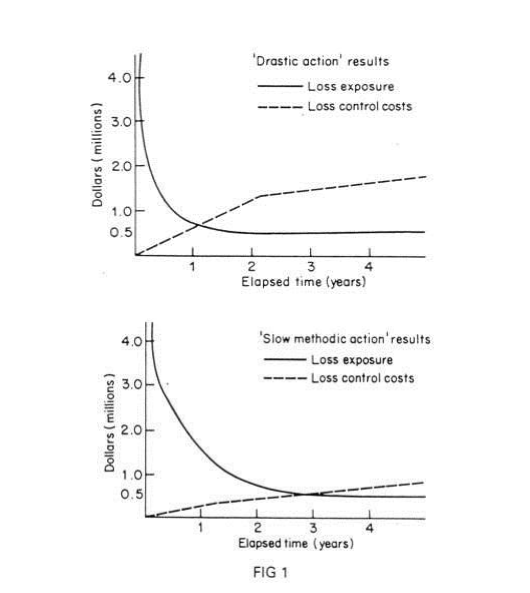

It was also observed that in almost all cases, quick, drastic action was taken in an attempt to remedy the perceived exposure problems. In most instances, nearly immediate results were noticed after the basic controls were in place, and then more "acceptable " levels of loss exposure were maintained for long periods of time after the "drastic action" was taken. It was also noted that within a few years of formation, the cost of controlling losses began to exceed the existing loss exposure. For the most part, "drastic action" was observed to be the quick hiring of sufficient personnel to physically attend all loadings and discharges of subject vessels, the establishment of a full scale loss control group including management, field and support staff, and the implementation of tight, although not necessarily complete or well planned measurement and accounting procedures. In those cases where “drastic action” was not taken, the corrective actions were slow but methodical, and the dramatic immediate results were not seen. In virtually all cases, loss exposure was reduced to “acceptable” levels within two years after the implementation of the loss control programs. (See Figure 1).

Thus, it can be shown, that loss exposure can be controlled if appropriate action is taken. If this is the case, then we do see so many loss control groups today (5 – 10 years after their formation) losing their effectiveness, drive, and direction? Why are seemingly controllable losses again starting to get out of control? Are loss control groups a self -destructing species that have seen their time and because of the inherent nature are doomed to ultimately fail, or is there something else on their development which causes this problem?

The answers to these questions is not simple; but the problem can be defined. We have already observed the two actions predominantly taken by the industry when faced with their individual loss exposure analysis which was either drastic or slow. Those entities taking drastic action were shocked into such a course by the "large loss exposure" reported, and they wanted to take any steps necessary to reduce such exposure and to safeguard their managerial position. Typically, they reacted with a "shotgun" approach, "shooting" all the reported problems at once and getting some immediate "spot" results. Managers then did an excellent selling job on the benefits of establishing a full loss control group and of raising the specters of growing loss exposure if such a group and appropriate budget was not approved. Once the budget based on the loss exposure reductions requirements, was developed, it was ramrodded into place and the groups set out to reduce losses.

While the survey confirms the initial positive results, groups started in such a fashion almost always ran into trouble within a few years. Unfortunately, because management wanted to react quickly, they did not take the time to plan their "loss control strategy" or weigh all possible options.

Once the stop-gap measures taken start reducing losses, management often feels that they need not look further towards problem solving. They believe that the "shotgun" approach will work for all aspects of the problem and most times fail to comprehend the dynamic nature of true loss control. Loss control evolves from certain actions required to be taken to physically stop the immediate outflow to the fine tuning of loss control by the use of contract terms and claims processes. They failed to allow for change!

In addition, the sudden onslaught of loss control staff with vague responsibilities and objectives, more often than not crossing departmental lines of authority, frequently cause much friction between groups, making working conditions and cooperation between departments more and more difficult.

After the initial loss exposure report is issued and the first action taken to reduce the described exposure everyone in the organization tends to back the concept and do whatever is required to reduce such frightening exposure. Thus those people working in the loss control area are looked on initially as 'special', but as time goes on, the novelty wears 'thin' and the special are soon looked on as nuisances and loss control groups become targets of budget cuts unless the positions are continuously justified.

They usually did such a fine sales job in 'selling' the loss control group that it becomes entrenched in internal politics, and then, once fully applied, the company can become 'saddled' with the group and overheads not necessarily fitted to solve the problem. Figure 1. shows the economies of scale of how after one or two years the loss control costs often outweigh the apparent losses, so in order to continually seek out new losses to prevent and continuously point fingers at reasons for loss. Management often fails to realize that it is in many cases just the sheer presence of the loss group that has reduced the loss exposure and that the justification of their existence should not be tied directly to actual loss exposure at the time.

Herein lies the problem within the design of most loss control groups. What is needed to prevent these problems? What can eliminate oversell? high fixed overheads? internal friction and resentment? Frankly, within a highly political corporate environment maybe nothing can prevent such problems because they are all very much politically related. However, within a management - oriented environment such problems can be headed off before they start; by first completely following through and reviewing the loss exposure evaluation. A company must not be 'frightened' into action; it must take a sound management approach. Once the evaluation is completely understood, a plan of action must be developed, which will include ways of taking stop-gap measures to reduce losses immediately, but at the same time not overly to build up staff.

The importance of proper planning of a corporate loss control objective and strategy cannot be emphasized enough. For without proper planning, no system can efficiently run and a system as complex as oil loss control will ultimately fail.

Six items must be included in the planning process, namely:

1. Premises. What are the assumptions about environmental opportunities and obstacles as well as existing organizational strengths and weaknesses relative to the loss control functions?

2. Purpose. To what end will the loss control group exist? A clear formally written and publicized statement of the group's purpose is the main focal point of the group's activity. The statement must be more specific than saying the purpose is to reduce losses. It must go on to give specific goals and objectives of the group.

3. Philosophy. A group can take one of several paths to accomplish purpose. Management can act honestly and in a straightforward manner, or it can use deception and fraudulent dealings to get the job done. In the long term, however, conforming to the ethical expectations of the culture in which it operates will enhance the changes of long term acceptance.

4. Priorities. Goals and objectives must be ranked in order of importance, thereby allowing appropriate emphasis to be given where it should and reducing 'wheel spinning' activities.

5. Procedures. Written or oral procedures for handling specific and extraordinary loss situations must be prepared, issued, and updated routinely.

6. Plans. These must tie all the loose ends together as a specific course of action, consisting of objectives and action statements whereby objectives are the ends, and the action statements are the means of executing the overall plan.

In other words, a clear program must be developed that allows management to say, "This is what needs to be done, this is who is going to do it, and this is how we will measure performance. Success is expected; failure will not be tolerated."

Simple, proper planning, however, cannot be the end but rather the following resolve and continued commitment must also be had by management in order for the loss control group's efforts to be maximized and its full potential realized.

MANAGEMENT COMMITMENT

Management must fully back a loss control program in order for it to succeed. The plan must be discussed frequently with supervisors; a mere issuing of a policy manual on the topic cannot suffice. The loss control program must become an integral part of the manager's responsibility.

CLEARLY DEFINE AND ASSIGN RESPONSIBILITIES AND ACCOUNTABILITIES

Without proper authority and lines of communication, the various elements of a loss control program stagnate. Such stagnation causes untimely loss reporting, poor claims follow-up, disregard for every procedure issued, etc., all resulting in unmanageable data.

Management must take full responsibility for this type of situation and top management must understand the direct connection between loss control program results and overall bottom line results. Those who do, assign such loss control performance to line management, and is an item on which a manager's overall performance should be evaluated.

UNDERSTANDING THE ROLE OF LOSS CONTROL STAFF

Loss control is sometimes considered the responsibility of the loss control group only and sometimes no one else in the organization invests any significant energy in the effort; loses that occur are blamed in the loss control group. An effective loss control effort should involve every segment of any organization. Hiring practices, accounting transportation, storage, all are involved in the loss control process and, once this fact is appreciated, the idea of a loss control program carried on exclusively by a staff function becomes unthinkable.

SUPERVISORY INVOLVEMENT

Supervisors involved in all field activities must be adequately used in the loss program. If not, management will fail to take advantage of the fact that the supervisor has the most influence and control over his employees' attitudes and work habits. The supervisor is the one most familiar with day to day operations, conditions and work environment and is in the best position to handle loss problems and take action as problems occur in order to lessen their effect.

THOROUGH INVOLVEMENT OF ALL EMPLOYEES

When all employees are not involved, the best that can be expected is apathy, which can degenerate into hostility and resistance to necessary changes which will make the program work. It is not sufficient to tell all employees within the organization that a loss program has been developed and implemented. It is quite necessary for all employees involved in the rated areas be told how the program will directly effect them, and how they directly effect the program.

Direct input and interaction from field and office often turns a 'paper program' into an operating success by tempering it with real world experience.

ADEQUATE TRAINING

Top level management must be 'trained' to understand the need for investment of time and dollars in loss control so that the necessary management commitment will be made.

Line managers must be well versed in loss control theory and practice so that incentives may be programmed to match existing needs and operating practices.

Supervisors must be trained in the basic elements of an on the job loss control activity, whether it be field or office, or accounting, so that they can properly supervise the plan.

General employees must be made aware of their role in the overall program in order to use the best reporting and accounting techniques and to be 'loss conscious'.

The training should probably start with those who will be asked to assume the loss control program management or coordination responsibilities. Adequate training is far more cost effective than throwing the learner into deep water, and hoping the student will quickly learn to swim.

Supervisors would naturally next assume that management is totally sold on the loss control idea. If employees are to learn and to understand both the importance of loss control practices and the significance of the roles they play in the overall practice, they will learn their best with the help of their supervisors.

A successful loss control program places the demands on just about everyone in the organization, from top to bottom. People will be expected to perform and to assume that people will be able to deliver this performance with preexisting knowledge and skills is wishful thinking at best. They will need training.

CONSISTENT FOLLOWING TO SET PROCEDURES

Procedures developed for the loss control program must be consistent throughout the organization- at each location and with all personnel. It must become a fact with all personnel including supervisors and managers as well. If not the program will not be taken seriously and the results will not be what is expected.

One of the best ways to achieve uniform commitment is to have the personnel involved in the development and carrying out of the program.

UNDERSTANDING OF THE INTERDEPENDENCY OF THE PROGRAM ELEMENTS

It is not unusual to see loss control efforts aimed at only a few of the key factors such as accounting or measurement. The justification of such an approach is the time and money are not available to do everything. In reality, such halfway measures may ultimately waste time and money that were originally meant to be used. A partial system simply cannot be expected to provide as much consistency and cost-effectiveness as a whole system.

A loss control program is really a whole system of elements, operating within a larger system, the overall organization. Systems theory tells us that all the subsystems depend on one another, just as the whole depends on the parts. Failure in anyone subsystem can cause both problems in other subsystems, and problems for the whole. It is the management's responsibility to see to it that all elements pull together to achieve both loss control program objectives and the objectives of the overall organization.

Not that a loss control program cannot be built up, step by step, one element at a time like a bridge. It can be. But like the bridge under construction, the loss control program in the making, must be carefully designed, with special attention to a first - things - first approach, and must be provided with extra support until such time as the last subsystem is in place and the program is operating and functioning as a whole. Actually, because of the human element, this is a never- ending process in loss control program management.

CONCLUSION

As the foregoing discussions indicate, truly effective loss control does not come easily, and although many systems in existence today are apparently doomed to ultimate failure, it does not have to be that way. The road to real results is strewn with good intentions, wishful thinking and beautifully designed projects that simply did not produce results. As with any other endeavor an organization chooses to undertake, loss control results will come, and the group will remain effective, only with intelligent, aggressive, persistent program management.